The Beatles, Hippies and Hells Angels features in Broadcast, British Media Industry Journal

‘The Beatles Hippies and Hells Angels’ was the subject of a feature of Broadcast, the British television industry journal.

I couldn’t believe my luck when Jago Lee asked me to make a film telling the inside story of Apple Corps, the fashion and music company set up by the Beatles. It took me a nanosecond to perform the necessary risk-assessment calculation any director does before accepting an offer.

As to whether the result would be any good, one has to imagine in advance what you will and won’t get from a film like this.

There were significant known obstacles. We were almost certain not to get the co-operation of the surviving Beatles, nor Apple, which would mean no original Beatles recordings or performances.

They like to control their story editorially, and take the profits that come from telling it. But I have never liked ‘authorised’ docs, as they always lack an edge.

And Apple Corps is not quite the same as the Beatles – it is probably the one chapter in their story you could tell without featuring the band’s music.

Apple Corps had a fashion store, an electronics department, a poetry label and a record label, featuring artists signed by the Beatles. Much of the label’s music, by artists like Badfinger and Jackie Lomax, could be used freely under Sky’s blanket music agreement.

As we entered the research and scripting phase, I quickly settled on telling a mix of stories about the company while leaving the Beatles themselves on the side. Interviews could be a problem, but as Apple had employed around 50 staff, I hoped that a decent number of them would talk.

As it turned out, the surviving top tier of management did not agree to be interviewed – at least one of them put in a call to Apple first to see what their position was. But many colourful people from the lower levels – engineers, assistants and secretaries – wanted to tell their story.

In fact, the co-operation of some of them had already been secured in the development phase. Many more were eventually persuaded to take part, sometimes over months, by producer Tom Jenner and assistant producer Gurbir Dillon.

In any case, there was already a film in the works about the Beatles: Ron Howard’s Eight Days A Week. We needed a bigger message to make the film feel epic and important.

This was to be both a kind of coming-of- age film and a doc about the perks and pitfalls of hippie-dom. The characters – by which I mean my interviewees – experienced a brush with fame in which, at least partly, their idealised images of the Beatles fell away. The band themselves discovered the pitfall of being a rich hippie: that your friends take advantage of you.

Peace and love

The historical story was the hippie movement of the late 1960s – this naive peace-and-love moment that led to disillusionment.

It had a simple narrative arc, as long as one juggled the chronology a bit: Apple was launched and moved in phases from disorganised optimism to weird anarchy. There was a climax to this process – a Christmas party during which a Hells Angel swung a punch at John Lennon.

After that, the Beatles brought in a tough new manager, downsized Apple, dumped the hippie ethos and then the band split up.

Finally, the film has a journalistic ‘revelation’: people say that the Beatles split because of friction involving Yoko Ono and Linda McCartney. In fact, it was the termination of Apple’s hippie multi-media ethos by manager Allen Klein that led Paul McCartney to pull out of the band and thereby end it.

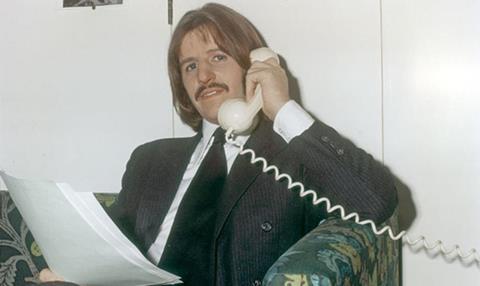

It seems that about five or six weeks into any production, I always find out a couple of odd things I didn’t expect, which can transform a film. Here, we found a couple of amazing archives of photos taken inside and outside the Apple offices from 1969, only around five or six of which had been seen more widely since the 1960s.

All of my main interviewees were in these photos. What a godsend.

Another was that legendary San Francisco hippie, actor and voiceover artist Peter Coyote had visited Apple in 1968 with some Hells Angels friends and gone to their infamous Christmas party.

My execs really wanted a witty charismatic voiceover. I had used one in my recent film Chancers, which Jago had seen, and which persuaded him to hire me for this.

Generally, I am not a big fan of voiceover – it is usually only there so TV viewers can still hear the story while they make a cup of tea, and few good documentaries use it – but I had always wondered if there was a way to make it good and imaginative. After all, it works in my two favourite films: Taxi Driver and The Big Lebowski.

So I settled on Coyote as an interviewee- protagonist-narrator. He frames the whole film and delivers the historical and universal message of the film, one he has lived out and believes in.

I wrote a list of plot points and tried to get every interviewee to tell us how they were involved.

When I rolled into the edit, I had 20 interviews, heaps of archive, hundreds of photos and some live performances to wrangle into a coherent 90-minute narrative. It was an enormous jigsaw and I was lucky that the Sky commissioning editor James Quinn and my producers were patient with me.

The edit is always a chance to take the film onto another level creatively. I brought on board Dutch New York-based animator Fons Schiedon, with whom I had previously worked on the Peabody Award-winning Poor Us.

Fons and I developed a green apple space-ship that floats and wobbles through the film, a bit like the yellow submarine. Devices like this help to create an intense, almost dreamlike, effect, immediately placing the viewer amid their Beatles memories.

Animation also helped because the main action scenes in this story were neither filmed nor photographed, and I needed to show them and make them exciting.

The archive caused some headaches. The Beatles have a performers’ copyright claim on any press conferences they were in. We needed a couple of clips of them as well as a few seconds of the Apple-produced Magical Mystery Tour to review and criticise.

Sky bravely agreed to accept a small amount of fair-dealing so we could use some archive, which was essential for the story.

Finally, there was the score. I wanted something contemporary and trippy with Beatles-esque motifs. “The Mad Professor meets the Fab Four,” I said to composer Adem Ilhan, who duly obliged.

We combined his score with obscure but brilliant covers of Beatles songs. I had always loved The Crusaders’ jazz take on Hey Jude and The Meters doing Come Together, but Bill Frisell’s version of Across The Universe was a revelation.

What a pleasure it was to lift the audio and hear him strumming “nothing’s gonna change my world”, over photos of Apple’s spaced-out employees, pupils dilated, staring at budgerigars or crashed out on the office sofas.

Recent Posts

- Did Qatar’s Courbet acquisition short-circuit French export licence process?

4 February, 2026 - The dark art of the deal: the oligarch who lost a billion in the art market

3 March, 2025 - Ballet dancer, Bond villain and bold painters: the art of the Trinidadian brothers best-known for their work on stage and screen

3 March, 2025 - Word of God – BBC Podcast Series about the Museum of the Bible, American Evangelical Christianity and Looted Antiquities

19 February, 2025 - ART BUST – my new podcast series about crimes, scandals and dodgy dealings in the art world

15 July, 2021 - Salvator Mundi becomes Salvator Metaversi NFT to raise money for original owners

15 July, 2021

Recent Posts

- Did Qatar’s Courbet acquisition short-circuit French export licence process?

4 February, 2026 - The dark art of the deal: the oligarch who lost a billion in the art market

3 March, 2025 - Ballet dancer, Bond villain and bold painters: the art of the Trinidadian brothers best-known for their work on stage and screen

3 March, 2025 - Word of God – BBC Podcast Series about the Museum of the Bible, American Evangelical Christianity and Looted Antiquities

19 February, 2025 - ART BUST – my new podcast series about crimes, scandals and dodgy dealings in the art world

15 July, 2021 - Salvator Mundi becomes Salvator Metaversi NFT to raise money for original owners

15 July, 2021